Rad Roubeni Is On Display

Photo by Steve Spagnuola @scuba1971

By Ash Hoden

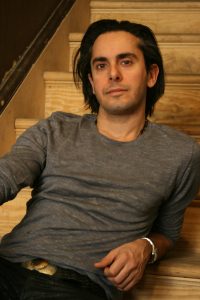

Rad Roubeni was born in Iran in 1978, the heat of the revolution. “And, being Jewish and being supporters of the king…” Weeks after Rad was born his parents sought refuge in Israel, then settled in West Germany where several of his uncles were established in life and in business. His father held no delusions about their circumstances, saying to Rad’s mother on the flight out that they would never be able to return. So Rad grew up in Hamburg.

I met him at an opening last summer and it wasn’t until I explained that Deviation is about those who are committed — how the Deviant’s Dictionary includes the word poseur for this very reason — that he became interested. When we sit to talk in his Tribeca artist’ loft, a space that doubles as a studio for his film, photography and design projects, he has much to get off his chest. His is the somber presence of one who has tasted the fullness of life but has yet to find what he’s looking for. He speaks quickly and evenly, unloading the twists and turns of his past with urgency. He wants to be heard. From the comfort of his sleek sofa I learn that his pursuits are many and varied, and the scale of his ambition is witnessed in the scale of his promotional efforts. When he goes, Rad goes big.

In Germany he attended an academically rigorous international private school, but struggled to keep pace. His dyslexia and ADHD didn’t jive with the classroom style of teaching and learning. “They didn’t really know how to teach the way my mind learns. So I always struggled academic-wise. Reading and writing, forget it. As much as I loved it, reading, it would take me years to read a book. Clearly I learn visually. With me it’s always videos and pictures.”

He explains by telling the story of learning Hamlet at his Long Island high school. His English teacher was sick and days before their test he told the substitute that he was dyslexic. “She said, ‘Listen, Kenneth Branagh just came out with the four-hour version of Hamlet in the theaters right now. It’s literally the full Hamlet script from beginning to end. No cliff notes, nothing. As accurate as Hamlet could possibly be on screen. It’s playing in one theater in New York City. Maybe watch that. It might help you for your test.’ So the night before my exam I literally shot out to the city, watched that movie, four hours, came back the next day, had the test — got an A. I would have had an F if I didn’t watch that movie. And the language they were talking in the movie, it was also the old Shakespearean English. It wasn’t like they changed it to normal English. It just shows that even something so hard for me to understand, even when somebody is speaking it to me, with all of the visuals and the understanding and the body language and… I was there. You know. The visual part helped me understand the whole story. I knew exactly what was happening.”

Photo by Steve Spagnuola @scuba1971

What a cool teacher.

“Yeah! She really saved my ass.”

In school, even in the earliest years, art was where Rad excelled. Drawing, painting, sculpting… All forms of visual media. “It was clear to me that art is where I’m going. It doesn’t necessarily have to be fine art but the creative world — and the visual creative world.” Film and photography were of particular interest and his school in Germany offered photography classes and taught dark room processing, but not until ninth grade. For Rad that wasn’t soon enough. When he was in the sixth grade he met with the head of the art department to plea his case. “Listen, I want to learn this shit now. So, what can we do?’ And he was like, ‘Alright, so, I’ll teach you.’ Basically the head of the art department became my mentor as far as photography was concerned.”

Through photography Rad tasted at a young age both the joys and pitfalls of putting your work on display for all to judge. His final project was a series of mug shots of his classmates with invented stories to go with the images. For one girl he wrote that she had been arrested for hijacking a bus full of nuns. For another it was a play on his classmate’s stature:

“This guy was one of the tallest kids in my grade. I shot him from his neck up and had measurement lines on the wall how they have it in police mug shots. It was kind of silly. Basically my whole entire grade was holding a number while I took mug shots of them. They went on huge frames and they were hung on a gigantic main wall that you see when you come up the stairs to the classroom hallways. Which was absurd for someone in my age to have. It was normally a display for upperclassmen. And I was a sixth grader. That’s when I knew that I wanted to be an artist.” Rad describes how he arrived at school to see a crowd of people standing in front of his work. “Having that gratification of seeing people being interested in something I created, no matter what the subject matter was. First thing I went to the head of the art department and he told me, ‘This is what it’s all about.’ I was inspired. I wanted to do more. I wanted to take my next project even further.”

Rad stayed late that day, putting in extra hours in the art studio, and when he descended the stairs on his way home he noticed that the photos were gone. “I went right up to the office of the department chair, ‘What happened to my pieces?’ He sat me down, ‘Listen, this is one of the things I hate. It’s not your fault. This is what we fight as artists. There were two teachers that thought some of the images were offensive. They complained and I had to take it down.’ And I was like, ‘What the fuck? Two teachers? People loved it.’ And he told me, ‘Yeah, there’s always going to be somebody complaining and artist’s work gets censored all the time. But don’t let any of that shit bother you. Keep doing whatever you want to do and it will come out.’ And he gave me examples of artists that were always pushing the envelope, like old Dada artists. People that just got censored their whole entire lives but they kept going and they’re some of the most influential artists ever known. So it kind of turned me into a rebel in a way.“

When he was fifteen Rad’s family immigrated to Long Island and he continued his education at a public high school. Adjusting to the culture was his biggest struggle. “It was a Long Island public school within a very nice neighborhood, so it was supposed to be one of the top five high schools in the nation. But you still had the class divide, which brought an uncomfortable segregation between races, cliques, and rich and poor students. And also being in a school with so many kids. I was used to a school where we all knew each other. It was a family in a way, even if we didn’t necessarily like each other. When I came here and there were hundreds and hundreds of kids it was more isolating. It’s kind of like New York City where you have all of these people and you would think it would be easy to make friends but its the opposite of what you expect. I didn’t understand the concept of it. I didn’t understand the concept of kids coming up to me and wanting to rob me. The whole mentality of the US educational system was completely different than in Europe, and that was just a hard contrast. All four years of high school — I thought it was a joke. It was almost like The Twilight Zone. I made the best of it at some point and figured out how to deal with this culture. I didn’t really advance much in an educational level but I had a great time as soon as I figured out how to deal with it.”

Photo by Steve Spagnuola @scuba1971

After graduating Rad enrolled in an art program in Denver but found that it wasn’t a good fit and his credits wouldn’t transfer to other art schools. So he took to the hills and spent a year in Colorado. “It was nice to live like a mountain man, doing tons of outdoors activities. I was snowboarding all of the time. Then I moved back to New York and went straight to Pratt Institute.”

When I ask about his experience at Pratt, Rad expresses mixed emotions. He had been accepted by all of the known art schools in New York but chose Pratt because it was possible to study multiple types of media and design, in addition to film and photography.

“Pratt kind of prides itself on kicking the shit out of you. Basically it’s like a military version of art. So much artwork until you can’t handle it anymore. By the time you come out you’re going to be tough as nails, as far as being an artist. The thing about Pratt which was kind of valuable but not what I was looking for — I felt Pratt for a long time was a mistake — is that it’s a very conceptual kind of school. It seemed that most students wanted to be gallery artists, and that’s it. I wanted to do high-end stuff and then I come to class and there are people taking pictures of their feet in their dorm and then putting it up and saying, ‘Yeah, the contours.’ This kind of shit. I probably would have been better off at a New York City art school where they put you in creative realms. You can be an artist but also have opportunities to be involved in other creative outlets besides being a gallery artist. You can work as a creative director at a company or work on a magazine or a production company or something like that. My school had none of that. I basically went to Pratt to learn how to be a starving artist. I had to figure everything out on my own, on that end.

“At no point did I say that I want to come out of art school and be a gallery artist. That wasn’t my intention. My intention was that, and maybe to become a fashion photographer, film-maker, or a designer. Fashion photography, to me, was art in many ways. You work with stylists and you come up with great images and stories and create an awesome visual. It’s kind of what I wanted to do but I wasn’t in the right school for that. But luckily enough my thesis was to have a gallery show. And the school only provided gallery spaces in the school — in downtown Brooklyn. It’s like, ‘Okay, you get this room for two weeks and you can display your art. Fill in your time slot.’ I’m like, ‘Fuck that. I need a show in New York City. It needs to be ground floor and I need to have the shit hanging for a month, like a proper exhibition. It needs to be accessible to anybody, not a few people who are going to make the effort to go to a deep part of Brooklyn to find a random room in this big campus.’ My determination was way higher than anything. I got really lucky by presenting my artwork to these people that had a nonprofit art organization, that I kind of knew from the club world. ‘Yeah, come by. We have a gallery in Times Square, ground floor, 6000 square feet.’ I was really determined to make that happen. Otherwise I didn’t see the point. I went and I sat down with them and landed a full-on exhibition.”

In Times Square?

“In Times Square, ground floor, 6000 square foot gallery, which worked really well for the series I had. Massive, very fashion-billboardy influenced. The show was called Rad Like Candy. I had thirteen to fifteen huge prints up and displayed for a month in Times Square. It went really well. About 800 people showed up opening night. The gallery supplied a team of people doing things such as PR and marketing and helping me set up the show. It was any young artist’s dream to have a show like that.”

You were 22 maybe?

“23. Right out of college and had this massive exhibition. A year later I moved into a loft that became my live/work artist’s studio where I could do film and photo shoots and more. I wanted to do film but I didn’t like where the digital world… I kind of stayed away from video for awhile and just continued with photography. Eventually those DSLRs came out, where you can shoot HD video with interchangeable lenses. So then I started getting back into film again and I started working with young filmmakers and started doing less photography. Obviously it’s not that easy to support yourself as an artist; to sell artwork. It’s always a struggle. And to live in New York City and the lifestyle I live… I obviously have to make money other ways. So I produce commercials, music videos, and documentaries.”

Rad earned his degree just as digital photography changed the market. “Right before I graduated the average photographer was making $100,000 a year. And then that plummeted. Photography became super competitive, and it kind of screwed me a little bit because I knew how to process film, which became irrelevant. Now you can just take a picture, throw it on the computer, and go Photoshop it and, boom, you’re done. YouTube videos and next thing you know you’re a pro. Everyone became a fucking photographer. That’s one of the reasons why I went away as a pro photographer. It took me awhile to realize the positive aspects of the field becoming so saturated. Photography in general became more exceptional, more amazing, and more influential. Even for me, although it made it harder to compete. It’s kind of a blessing because it let me explore other stuff.”

Photo by Steve Spagnuola @scuba1971

A new opportunity came Rad’s way a few years after Pratt. People he knew from the promoting days were planning to open their own joint. They approached him to develop the club’s overall concept, theme, and design in exchange for a percentage of ownership. “I was in Argentina for a couple of weeks and I got inspired by the Patagonian mountain culture. ‘Okay, I’m gonna make this club kind of like a mountain chalet on acid and call it The Retreat.’ It couldn’t just be a chalet. So I spent time in upstate New York with some hillbilly buddies who knew everything about wood. It was really expensive to get old wood and we didn’t have a budget for that. I thought, ‘I’m going to find my own wood. I bet you if I can find my own pieces, have it cut up in a sawmill, and bring it here, it’ll be cheaper.’ That’s exactly what I did. Me and this guy would go into the forest and find dead trees that were about to fall or were buried in mulch piles for who knows how long. We’d find the most fucked-up dead, rotten trees you could possibly imagine, take them to the sawmill, cut them open, and see if there was any cool detail. There were some trees for example that looked like pen and ink drawings through the tree. I literally just went nuts on wood, and just went logging with this guy. With the design that I had I needed certain things. It was amazing to find all of these different types of cool wood that I would have never imagined. It definitely gave me a new appreciation for wood. I found 150-year-old barn beams on the side of the road. We would just throw it in my friend’s pickup, drive it to New York City, and throw it inside the space and build it. I got these crazy antler chandeliers and painted them with red automotive paint — kind of like a glossy red lacquer.”

The VIP room was octangular. Each wall contained glass “window” frames mounted with eerie forest images that Rad shot and then constructed to have a stereo, 3D effect that he developed at Pratt. “I went upstate and I was in the forest, at night, and I did this photography project where I painted with light. Basically you have the lens shutter open in the dark. You can’t expose the sensor of the film when it’s dark, so if everything is dark and the lens is open it’s not creating an image. But I would run around with a strong flash and I would put color gels over the flash and I would just flash trees in different colors. I would literally paint this landscape of forests and just make these trees pop out in different colors. I didn’t want bright daylight forest. I shot during the winter too, so there were ice walls — these frozen waterfalls. I was shooting this ice and I was doing the same thing and crazy, color images would come out of that. So I created windows with trippie night forest landscapes.”

It was really hands on.

“Yeah, it was really hands on. I was literally there every day with these woodworkers and builders. In general the design was a huge success. Everyone that entered felt like they were in a cozy winter wonderland. It was definitely an interesting part of my life, for a couple years.”

From this experience Rad decided to get more involved with architecture and interior design. “Some of my family is in real estate and I approached two of my cousins who were developers and told them, ‘I’m interested in working with you on the creative and production side of the process and at the same time learn from them the other aspects of the business.’ I knew that all of the skills I use in film and photo production, as well as putting together other art projects, were directly useful in real estate development. It’s the same as a producer managing a crew or a major project; getting and working with directors, cinematographers, art direction, set builders, lighting, hair and makeup, etcetera.

“We were developing residential buildings all around Brooklyn, learning to understand the neighborhoods and the dynamics of living there. We would use that as the basis of all of our projects and work with all the subcontractors to make it happen. For example, we would find a land property, figure out what the market would be, what kind of people would live there, and come up with the best concept for the kind of dwelling that would be the most ideal. Besides figuring out the feasibility of the land with an architect we would figure out what kind of structure would best suit that piece of land in that neighborhood. The architect would give a clean shell with a few examples of possible layouts and I would use that as a canvas. It would help me come up with a design concept and I would draw it out. Then the architect would implement that into the plans, working together with the engineers to make it physically possible. In my mind the development process was almost like creating a humongous sculpture — that is functional.”

In this way Rad contributed to a couple of development projects, one of which was particularly meaningful to him. Their company bought a two-story single-family home that had been featured in Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind. The house was vacant for a number of years. Squatters had moved in and the interior was being stripped of its metal wiring and fixtures. “We wanted to keep it because it was kind of cool but it was a single-family home on two lots, which made it not very financially lucrative. We had to turn it into a sixteen-unit rental building, but we were very much about preserving the aesthetic of the neighborhood. It’s a very beautiful tree-lined street and we wanted it to look like it’s part of the neighborhood. That was the design task I had; to kind of let it mold into the existing style. The project was a big success. We wound up renting out every apartment before the building was even finished. It was the same feeling I had as a kid seeing people crowd around in front of my art. That feeling alone — it’s fucking awesome. People’s lives are in there. People are actually going to have memories of living in this place. It was very deep for me. I wanted to continue doing more projects like that but my film stuff was picking up, so it drove me back into film production.”

This is when you started showing again?

“The design company that I worked with was in need of artwork in their new offices. The main principals of the office wound up commissioning me to work on a series of artwork that would best suit the company’s ideals, keeping their industry in mind. Being that the company was heavily engaged in developing buildings all over Brooklyn, I took photographs of New York streetscapes that haven’t been developed yet — paying homage to the old look of New York and Brooklyn. Also, being really into street art I wanted to keep an element of that in the photography. I wanted to exemplify the fact that painted walls are what comes to mind when you think about many areas in the boroughs. So I shot for three months using a really high-end, massive, medium-format camera. Shooting high-res images in HDR to get a better dynamic tonal range, and then printing it on canvas because canvas gives it a little bit more texture. At the end of the day I wanted these images to be life size as if you were standing right in front of them.

“I created these images and had them stretched and framed and we hung them up in the design offices. After a few weeks I got so much positive feedback and interest that I got inspired to do more. I went ahead and created the artwork and in the process of doing the work my inspiration started evolving. I started noticing the ephemerality of each wall. As time goes by the walls evolve and look different. Not just people painting over it, adding new layers and textures, but also nature affecting the appearance of a wall or it being completely rebuilt or torn down. This gave more meaning to my whole project.

Photo by Steve Spagnuola @scuba1971

“Then I decided to have a show and arranged a two month solo exhibition in the Lower East Side, which I felt was a great success. Not only putting my work out there but getting even more inspired about what this artwork meant to people and getting really interesting feedback from street artists who randomly happened to have their work on some of the structures in the photographs. For some, being quite grateful about their work being taken from the streets into the fine art realm. I called this series Public Display NYC. This further inspired me to go shoot other cities around the world and extend the series. It’s very interesting because street art in all these different places has different meanings behind it. There’s social and political stuff involved. Maybe go back to my birthplace, Tehran, where there’s street art that talks about real serious shit. The problem is that I would probably be risking my life to document it. In most places street art is illegal, which makes it an even more important form of expression. Street art almost becomes its own language with its own character and meaning based on the history of each specific place where it’s created.

“It would be a dream to have a series like this in different cities around the world, and I hope to be able to do that soon. That’s when you learn one of the things that art is about for me. Is it about making money? Then you’re in the wrong business. It’s about passion and expression and feeling — having people being impacted by your artwork. It makes you feel good. You sparked emotion in someone’s life, and/or inspired them. And to make a living doing this makes it even better.”

Rad finishes with a bit of reflection. “Life has been an adventure. I always as a younger kid thought, ‘I’m going to be a successful artist or filmmaker.’ It’s not like I can just give up and go into finance. I can’t do that shit, regardless. I can’t sit in front of the computer and try to make sense of spreadsheets and statistics and all that stuff. Whatever I do it’s going to be in the creative world. So in a way I have no choice but to be an artist.”

Here I recall a Janet Fitch quote that a friend sent during the hot-and-heavy of putting this journal together: “I’ve told you, nobody becomes an artist unless they have to.”

Get Deviation Issue 001 (Print or Digital)

[fbcomments width="100%" num="10" ]