Morocco ‘Rocc’ Omari: Potential Meets Discipline

Photo by Christine Jean Chambers

By Ash Hoden

Morocco Omari entered my world at the right time. I had been a little too caught up in big worries over small things, such as work and money and making my way in new pursuits. But talking with him, then listening back and transcribing the recording word for word, helped clear my mind of its concerns. It was like meeting with a counselor, hearing him describe his life and how he goes about living it. There’s a calmness to his voice. Not only the sound but the substance; the essence that is being conveyed. Absorb what he’s saying and it will affect you. Several emotions surfaced while putting this piece together: joy, sadness, humility, admiration, respect, gratitude. I laughed, I nearly cried at times, I was quiet — just listening…

“Rocc” stars in Empire, the hugely successful television show. Part of his interest in talking with me is due to the fact that Deviation is devoted to the backstory. “Sometimes you need that inspiration. Because we really see the finished product a lot of the times. We see Tom Hanks and think, ‘Wow, I want to be that,’ but don’t understand how he got to become that. They don’t understand the grind it takes to become that.” Hearing Rocc share some of the history of how he became Rocc is an enlightening experience. It’s not often that you meet such a thoroughly complete individual. They say that the smart learn from their own mistakes and the wise learn from the mistakes of others. What is it when you bring clarity to another person simply by being who you are and expressing that? Inspiration?

Rocc was born in Chicago. He grew up on the west side. His parents were fifteen when he was born and they were both virgins prior to his conception. “First time out, bang, here I am,” he chuckles. His father worked and supported the family, but he left for college when Rocc was four. He and Rocc would reconnect about five years later. During his high school years Rocc moved in, living with his father and step-mother in Chicago’s north suburbs. “Which was a good idea, because — west side, there was a lot of drugs, gangs, violence — stuff that you normally get when you’re in certain neighborhoods or socio-economic [circumstances].”

Was it a struggle to stay out of that?

“Well, you know what, I got a pass because my uncles and aunts were like gang members or drug dealers. And I was good at playing football. Everybody knew me as an athlete and everybody knew me as so-and-so’s nephew. I really didn’t have to join a gang. I knew all of the gang members. I knew all of the drug dealers. My godfather was a drug dealer. I knew a lot of the guys. It kept me out of trouble. Plus, my dad was a martial artist so he taught me martial arts, and my stepfather was a boxing instructor so I learned to box. As a kid growing up, you know, I was nice with my hands. After a few fights then nobody wanted to fight you anymore. I stayed out of trouble. And I knew I had to go to college to play ball, so… I got to college, and got into trouble. How about that?”

I can kind of understand that though. In some sense when you’re in the thick of it you’ve got to stay straight. When you get out of it then you’ve got to learn how to do it on your own, and when you have that flexibility to cut loose it’s pretty easy to do it.

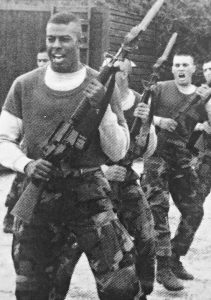

“You’re on your own, you’re eighteen, and you know, I was down in Jackson, Mississippi. If you were a man from Chicago, New York, and Detroit, the Southern girls loved you. We were wild. We did a lot of partying, a lot of drinking, got into a few fights. I was majoring in theater as a fluke. Growing up I was a class clown and all that stuff. You figure, ‘I’m going to go play pro football.’ You put all your eggs in one basket. That’s what I did. My theater instructor at the time, she saw me falling off and she called me to her office. I was a little cocky eighteen-year-old, going on nineteen, and she said, ‘What are you going to do with your life? You gonna chase women, throw parties, and drink for the rest of your life? You have potential but you have no discipline.’ It was one of those things where someone completely out of my family, someone completely out of my circle of friends, someone who barely knew me, saw me. You know what I mean. She saw me and she saw the potential. And for her to read me like that, to see that and say, ‘Are you going to keep doing this, this, this, and this? You’re better than that and you could be so much better.’ It hit me. ‘Wow. Ok. I can be better! I’m gonna get some discipline. I’m going to the Marine Corps.’ I went in as a reservist and I ended up fighting a war.”

You were playing football and you were in university, but her saying that—

“I got kicked off the team, yeah. My plan was go to boot camp, go to infantry school, go to engineering school, and then come back to school. But then the war broke out and I was over in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. You come back from that and… A war puts ten years on you. You feel like, ‘Oh, I’m an adult now. I feel like I’m thirty-years-old.’ Even though I was barely twenty. You had this maturity. ‘Alright, I’ve got to figure out life.’ While I was over there I was getting shot at, I was sleeping in the ground, stuff like that. I was on the front lines the whole time. My company, we liberated Kuwait. I was one of the few Marines that went through Kuwait and liberated Kuwait.”

No way.

“Yeah. We had heavily armored bulldozers, right behind each other. They breached the mine field to make a two-road highway, and then barb-wired them off so our convoy can go in. We went in in these five-ton trucks. We had tanks and everything — and we were getting shot at by mortar rounds. We stopped and called in the Cobra and Apache helicopters to take out these Iraqis, wherever they were shooting from. We literally took Kuwait within — it was less than two days. Because the Iraqis, the farther you were away from Baghdad the worse off you were. You weren’t getting any food, no communications… You were pretty bad off. Catching rainwater in red buckets… Going through Kuwait humanized me because I was running into Iraqis who were just like, ‘Hey, I’m a farmer.’ Or, ‘I’m a student. I didn’t want to fight. They came to my door, gave me a gun, and said, ‘Fight the Americans.’”

When he describes seeing the humanity of those he was sent to fight, the inhumanity is made much less abstract. I nearly break down, thinking back to some of the people I met while living in the gulf region. In the telling of it, Rocc humanized me.

“When you’re in a war, you’re like predator or prey. You’re stripped of all humanity. I was stripped of all humanity. Because you have to get over the fear of dying. Once you get over the fear of death, then you can live. You know what I’m saying. And we all had cyanide pills in our breast pocket, just in case we got captured. Pop that and you’re gone. It was a prize to catch a Marine. I was like, ‘I’m not going out like that.’ I remember writing my mom a letter saying, ‘Hey, I’m not throwing down my weapon. I’m not surrendering. I’m going to take as many as I can with me and, um, I love you.’ And that was it.”

Damn. Do you feel like you have come to grips with death?

“I came to grips with death in the first day of war. And that’s not to say that I’m reckless. It’s just that I’m at peace. I’m not afraid to die. It’s not like, ‘Let me walk down this dark alley.’ It’s just, I’m able to live life. I’m able to get on a plane and go to any parts of the earth and not be, ‘Oh, I’m afraid. I’m scared.’ Needless to say, I remember walking through Kuwait and the ground was shaking because of the bombs. I said, ‘Yo, if I ever get back in one piece I’m just going to follow wherever the universe guides me.’ So I came back to Chicago. I was working a job. I enrolled in a local school and I was majoring in business because I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. All of my friends were becoming cops and working in the prison systems and I just didn’t want to be a cop. I didn’t want to be a CO in a prison. I started modeling a little bit and then I started getting cast for commercials. Then I got cast in a virtual reality game. I was an extra. I had no lines. I’m watching the actors, and I was like, ‘I could do that.’ Still cocky. I went to one of the actors and said, ‘Listen, I don’t mean to get into your business, but how much are you getting paid?’ It was way more than I was getting paid. So I went to my agent who handled actors and models. I sat down in the chair across from her. ‘You know what, I want to be an actor.’ She laughed. ‘Oh, Morocco! You’re so funny.’”

Rocc does a great impersonation of his agent laughing at him, and I’m laughing as I’m listening.

“No seriously. She said, ‘I tell you what, take some classes, do some theater, and I’ll send you on auditions.’ I said, ‘Fine. Cool.’ I went down to Act One first, then I went over to Piven Theater, then I was at Second City, and I was at ETA, and then I got cast in my first play — in Evanston, a suburb of Chicago. And when I stood on that stage in front of that audience, the first night we had a live audience, it hit me. ‘Ohhh.’ The adrenaline was the same thing I felt on the football field. ‘This is what I’m supposed to be doing.’ I started doing play after play after play. And with the Marine Corps, the way we’re wired, I’d work from 6am to 3pm. I’d get off work, I’d go to the gym from about four o’clock to about six o’clock. Then I’d either go take a class, or I’d go to rehearsal, or I’m doing a show. So my day started at 6am, [and went] to about eleven at night. And I did that for five years. Straight.”

Did you have a different feeling about acting back when you were in university? You said that when you got on stage after the war, that’s when it hit you — ‘Oh, this is the thing.’

“When I was at the university I didn’t take it seriously. When I was growing up, no-one in my neighborhood was an actor. I’d watch television. I love Steve McQueen. I love watching Sanford and Son and Good Times and the comedians — Richard Pryor was a great storyteller. I didn’t know anybody personally who made money as an actor. I saw plays and all that, but I didn’t know that this is a career. When I was in school I didn’t understand, ‘Oh, I can do this for a living and provide for myself.’ Until I talked to the guy on set and I was like, ‘How much are you getting paid?’ Then it clicked. ’Oh, hm, ok. Alright. You’re an adult. And, ok. You make that kind… Ok, you make that kind… Ok, I can, I can, I can do this,” he laughs, describing how it all solidified in his mind.

“So, I did that for five years and worked at some of the bigger theaters here. Every year I’d write down what I wanted to accomplish. I want to work at Steppenwolf. I want to work at Goodman. Or I want to work at Victory Gardens Theater. Or I want to get my Screen Actor’s Guild, or my Equity Card, or my AFTRA Card. Every year I was crossing out all of the stuff I wanted to do. After I did that, my agent said, ‘Listen, there’s nothing else for you to do here.’ I moved out to L.A. in ’99. I continued to train. I wrote my first film. I was on the set of the show called Judging Amy — and I was just writing because I was playing opposite of Rosie O’Donnell.” She had a lot of dialogue, leaving Rocc with plenty of down time on the set.

“I think I wrote this movie in two days — it’s a twenty-minute film called The Male Groupie. I’m not a great typer, so I typed it up with two fingers. Shot it in three days. It went in a lot of film festivals, it ran on HBO… Like, the first film I wrote ran on HBO. It was crazy. ‘Ok, I guess I’m a writer.’ But looking back, I’ve always been an entertainer. I’ve always been a writer. In seventh grade I won a writing award and I went to the state championship. I came in third for the state. In my school I was like the dude, the writer. I’ve always been a writer. I used to write love letters in the Marine Corps. People used to pay me to write love letters to their girls.”

No way!

“So serious. Just because of the imagination.”

Were you focusing mostly on TV and film work in L.A.?

“Yeah, because it’s not a theater town. I did one play in L.A. in the seven years I was out there. I’d come home to Chicago and do theater. I’d come to Chicago to work out. Theater keeps you the sharpest. It keeps you really sharp.”

Being live.

“You don’t get any second takes, man. It’s funny because I was at this festival in Chicago. This lady she came up to me and she was like, ‘I know you. I saw you in a play at Steppenwolf.’ And this play was twelve years ago. I was like, ‘Whoa, you remember this performance from twelve years ago?’ That’s probably the biggest complement.”

That’s amazing.

“That’s how I feel when I see actors on stage. With good art, be it acting, singing, musicians — you remember their performance.”

What pulled you out of L.A.?

“I went through a divorce in ’06, and my oldest daughter wasn’t doing well in school. I was just like, ‘Let me go home. I’ve sacrificed a lot, you know, the father-daughter bond. So let me go home.’ HBO paid me nicely for Male Groupie, and I bought a condo and I moved her in with me. I figured I could still do what I needed to do and I had big family support in Chicago. It was more family than anything. And then there’s an undercurrent in L.A. that’s just very, very fast. I didn’t buy into the whole networking or sleeping with people to get jobs, or anything like that. I didn’t feel like I needed to conform. I can’t put on the fake smile, ‘Hey!’ Talk in my high voice, and all that. Really, it was like, ‘Man, listen. Let’s just do the craft. If you think I’m good enough to do the role, cool. But I’m not gonna make you feel comfortable and you know…’ L.A. is L.A.”

I’ve heard of the casting couch for women. I don’t know why, but I didn’t think about it going the other way as well.

“Oh, it does, it does. It’s equal opportunity.” He enunciates the words and it’s hilarious. “L.A. is wild man. It’s wild.”

Did going to Chicago help with your family?

His voice softens a little. “Well, yeah man. We turned her grades around and everything. Yeah. It helped.”

Did you have to start again in Chicago or were you established enough?

“I was established enough. I just called my agent in Chicago and said, ‘Yo, I’m coming home.’ Chicago has respect for art. If you’re good, you work. If you’re not a prick or anything like that. I’m real cool, laid back, man. My relationship with the theaters was just, ‘He’s easygoing. He does his work. He goes home.’ I don’t show up drunk or high trying to do the work. I’m laser-beam focused.”

Being good to work with is important.

“Because you figure, you do a movie for like three months, right. You’re on location somewhere and you’ve got a couple of actors who are just babies, making it hard. ’When am I going to shoot? Oh my god it’s too cold, it’s too hot. Oh my god!’ You’re just like, ‘Dude, this could be so much easier.’ Because I’ve directed films. I’m thinking about the shot, I’m talking to my cameraman, I’m making sure the actors are comfortable, we’re making sure we’re on time to get this day. All this stuff is going on and all you have to do is your role and be cool, you know. ‘Relax. We’re not curing cancer. Let’s just have a good time and shoot the movie.’ I just sit back and chill, man. I appreciate everything I work on. I bring my reading material, my writing material, my laptop. On the down time I’m writing, doing something creative. You’re not just going to show up and shoot. They tell you to show up at noon, you might not shoot until eight that night. You’re gettin’ paid, you know. I always remember sleeping in a hole with bombs going off. I’ve been to hell man. I’m havin’ a good time. That’s why I don’t complain about shit, man. I know what it’s like to go through it. You know, to go through it.”

The first time he says this I read it to mean “endure.” But when he repeats “go through it,” again stressing the word “through,” I hear it as a statement of transformation; passing from one form to the next. Rocc was saying both. Very eloquently and deliberately he was making me see. He had endured, and by doing so he had been transformed. The force of these two simple enunciations levels me. Petty everyday worries that the majority of us routinely obsess over are of little concern to him. He has gone through that stage, and now occupies a much higher one. Both personally and professionally. He concludes his thought: “For me to complain? Nah, man. Nah. I got a second lease on life. Complaining ain’t gonna do shit. It’s not gonna do anything to put that out in the universe.” This statement settles in my thoughts, then expands outward into the city, the earth, the Milky Way, and the universe beyond, its veracity growing stronger and stronger the farther it gets from my own minuscule place in the overall.

How were the roles that you were getting in L.A.?

He takes a breath before speaking. “I mean, if we’re being honest, a lot of times when you’re seeing “the black character” on television, he has no life. He has no wife. He has no backstory. So if you’re doing a guest star, you just come in… I play a lot of authoritative roles because, you know, military, I guess the way I carry myself, my voice is deep, I’m kind of tall, I got some muscle on me… So I play a lot of cops, detectives, bad guys. A lot of times they’re not really writing for you. You’re just keeping the wheel moving. Say your stuff and get out the way, pretty much. Which is the great thing with my current job. I’ve got a lot of meat. They’re really trying to develop this character as much as possible, which is great. I always tell actors, if you’re prepared writer’s will write for you.”

Do you get to put your own writing in there or do any improvisation?

“How can I say this?” He’s thinking about how to describe something delicate. “I live in Jersey, my character is from Philly, he lives in New York. Empire takes place in New York [but it’s filmed in Chicago]. A lot of the lingo changes really fast, so what we’re saying in Chicago or what a writer from L.A. might write, won’t necessarily be what we’re saying in New York. So I’ll write something — not to change the whole scene, just give something a little bit more color; keep it a little hip, a little current. And they’re really cool about it.”

Are there any positive moves toward developing more black characters that have more depth in general? Or is it still ongoing — the majority of roles have no background?

“There are a lot of good writers out there who are writing good stories, who are writing good content. Now, whether the networks will buy into it? I mean Shonda Rhimes is doing really well, with her 42 shows that are on TV. Kerry Washington has a great storyline. Viola Davis has a great storyline. It’s coming. It’s slowly coming. Some of the movies, yeah… There’s content out there. It’s just a matter of getting them made, if that makes sense. You have to convince a lot of people in suits that people will like this art, because they’re looking at the numbers or they’re testing it with a test audience. They didn’t think Empire was going to work. And it just exploded. It exploded, man.”

How did you get into it?

“I auditioned, actually. It said ‘Star Names Only.’ Right. ‘Someone who can match Terrance Howard for alpha maleness. Star Names Only.’ I was like, ‘Well, they’re not looking for me.’ So when I did my audition, I put it on tape for Leah Daniels who is the creator’s sister. She’s a casting director out in L.A. and she’s always been loyal. Sometimes I’d go into a Jamaican dialect and I was just putting my own words in there. I was like, ‘Send it. I’m not going to get it anyway. I might as well have fun with it.’ My agent in L.A. called me. ’Dude, you’re the first choice.’ We had to get approval from the executives, then the studio, and then the network. All from my tape. Usually you have to fly out to L.A. and test. I didn’t have to test. They saw all that stuff, I’m sure they looked up my credits, and I got the role.”

How long ago was that?

“We’re going into season three and they introduced my character the last three episodes of season two. So, guns blazin’ baby. I wasn’t supposed to be Terrance Howard’s half-brother. I was just an FBI agent coming to investigate them; try to take ‘em down. After the first day on set all the producers were like, ‘Oh, he and Terrance Howard kind of look alike. They could play brothers.’ So they wrote that in, that we’re half-brothers. Now I’m an FBI agent who’s his half-brother and is also trying to take him down.”

The drama teacher in university really did see you.

“The funny thing is, ten years later she was teaching down in Montgomery, Alabama. I was doing a show in Montgomery — in the Alabama Shakespeare Festival. My girlfriend at the time, who became my wife, had just worked with her. One of our first conversations was about that story. She’s like, ‘Oh, that sounds like Doctor Stewart.’ I was like, ‘That is Doctor Stewart!’ She was like, ‘I just worked with her on this show.’ I said, ‘Really? Where is she?’ She’s in Alabama. ‘Wow, I’m about to go and do a show in Alabama.’”

Rocc devised a plan in which his girlfriend would fly to Montgomery and convince Doctor Stewart to go with her to the opening night without saying that Rocc was performing. He tells the story with laughter in his voice. “She thought I was crazy. ‘Dude, I just met you. What makes you think I’m just gonna fly down to Alabama? You don’t even know me.’ I was like, ‘Nah! This is what’s going to happen.’ So she came to Alabama and convinced my teacher to come to opening night.” Rocc’s plan worked perfectly. “After the show, I walked up to her, and I was like, ‘I just want to thank you.’ She just started crying. So ten years after that conversation… It’s crazy how my life happened.”

No kidding.

“Sometimes you just listen. You listen to the angels, man. You listen to the universe. I was lucky to have her tell me that.”

One person can really change things.

“The butterfly effect. Yeah.”

Do you still do martial arts?

“I’m about to get into some krav maga. I got a little free time. I’m like, ‘Let me get back, ‘cause it’s been a minute.’ It’s been a minute. Those muscles tighten up! If you don’t stretch, man, those muscles tighten up,” he laughs. “But that’s with anything. Acting is a muscle that needs to be exercised. You have to work it. I tried to get on stage — I had taken off like three years from theater and I tried to get on stage — and I was getting my ass kicked. I didn’t have that deep breath support, that diaphragm. I was struggling. I was walking down the street like a crazy man saying my lines. When you do TV and film you get lazy. You have a couple lines here, a couple lines there. When you do a play you might have a two, three-page monologue, or real dialogue. This play I was doing, I was saying poems and stuff like that the whole first act. So I had to learn all of that. I was just, ugh, the breath support.”

There’s a physicality to it.

“Physicality,” he repeats the word like he’s playing with it, sizing it up and enjoying it a little. “Physicality, you know. My mind knows what it wants to do but my body’s not doing it. And then you’re on the stage with theater actors. It’s like if you run up into a marathon and you haven’t run a marathon. You turn around to see these Kenyan and Ethiopian cats, you know what I mean. I was in the gym on the treadmill, running, saying my lines. I was just trying to get it. It was a valuable lesson. ‘Ok, you can’t let it go.’”

Were you mostly doing theater during the time between L.A. and getting on Empire?

“I was doing TV too, but I would still get on stage at least once a year. I was in Denver last year doing a play. That was a learning experience because of that altitude. I would fill up my diaphragm,” he takes a deep breath and proceeds to show me the technique, “and say my lines while slowly letting the air out of my diaphragm so that I would not lose my breath so I could keep talking and saying my lines without taking a breath because of the altitude and the thin air and I could talk and talk and say my lines and take my lines without taking a breath.” He says the entire run-on sentence evenly in a normal voice and you have no sense that he’s losing air or speaking on one breath. “I had to break the script down just like that. It was good training.”

What’s one of the most impactful lessons that you learned?

“Wow, there’s so many.” He pauses for a beat. “Staying on your path and believing in yourself. People get into their art form thinking that it’s going to happen over night, and it’s not going to happen over night. But if you keep plying your trade and you stay on your road and you keep putting in the work and you continue to grow, it’ll happen. It might not happen when you want it to happen. It might not happen when you think it should happen. Just keep walking forward. That’s it. Keep walking forward. And another thing you have to do: you have to enjoy the journey. You have to appreciate every accomplishment. You have to appreciate every day. Because when you get to where you think you want to be, if you didn’t enjoy the ride, you’re not going to enjoy the destination.” It feels as though he’s speaking to my soul at this point.

It kind of goes back to having the freedom to live. There’s no worry about where things are going or what you’re doing. You’re alive — you’re free to just keep going.

“Yeah, definitely. Definitely.”

And enjoy it.

“It’s like both sides of the journey. I was in the damn war. You’ve just got to laugh. ‘Shit, ok. That’s funny. It sucks, but it’s funny.’ Everything wasn’t funny, but you’ve got to find the laughter in life. I could be a paraplegic. I could have come home with no legs, man. I’m just like, ‘Yo, I’m healthy, I’m in good shape, got a decent mind, and whatever I want to achieve, if I put my mind to it I’ll get it.’ The mind believes what you tell it. If you train your mind, and say, ‘Ok, I want to do this.’ If you focus on doing that, the mind will pull you there. But if you put all of the negative thoughts in, ‘Aww, this is going to be a fucked up day.’ Then it’s gonna be a fucked up day. So it’s basically training the mind. ‘This is how I want to do it.’ And you go get it. Anybody that’s great hasn’t been afraid to fail. When you fall, then you get up. Keep going. Keep walking forward. Don’t let success go to your head, and don’t let your failures go to your heart.”

Photo by Amanda J. Cain

Yeah! That’s good.

“Live by it. Anything I win, any awards I get, I give ‘em to my mother. I don’t want ‘em in my house. I don’t want pictures of me in my house. I stay hungry. Yeah man. I stay hungry. She’s got all my medals from the Marine Corps too. I don’t need it. The biggest reward for me is when a woman tells me she saw me in a play twelve years ago. That’s how great that was. I don’t need the awards. I mean, I’m grateful to get it. You see me at the Oscar’s crying, ‘Awwww…’ It’s just — that was a journey. I did my first play twenty years ago. Appreciate it, stay hungry, and walk forward. As a writer, I’m trying to outdo what I wrote on the last page. Or I’m trying to outdo what I wrote last time. I’m trying to flip it up. What can I do to make it better than that last one?’ It’s kind of daunting and intimidating, but that’s how I am with life. You want to raise the bar every time.”

Page by page even.

“Page by page. Yeah.”

Get Deviation Issue 002 (Print or Digital)

[fbcomments width="100%" num="10" ]