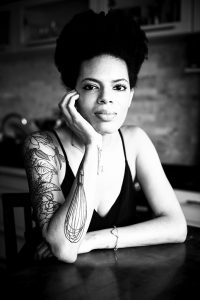

Melinda Hanley is Happy to Suffer and Endure

Photo by Chris Keohane

By Ash Hoden

The dynamic shifts when you place a smartphone on the table midway between yourself and another person, pressing the record button and proceeding to talk as though it’s not there. No longer is it a casual affair, shared words irrupting and dissolving in real time with only faulty, lapsed memories keeping score. We are now creating history, capturing in abstract time even the subtlest intonations, documented word for word. Nothing is lost. And as any good conquerer knows, the power to write history is a spoil of conquest. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

I sit before Melinda Hanley knowing only that my intentions are pure. She sits before me knowing that she has much to say, but that any word she speaks has the potential to be misused — intentionally or through carelessness. Once the words are vocalized they are documented. It is a power dynamic, and power can be abused. She must consider whether my intentions are in fact pure, and whether I am capable of appropriately handling the intimacies she chooses to share. In other words, she must decide whether or not I am worthy of receiving and transmitting the power of her history. The risk is all hers.

The first several minutes of our talk are biographical. Melinda gives me the rundown: raised in Indianapolis; earned a bachelors degree in art history and fine arts from Purdue; worked for five years at various art-related nonprofits in Indianapolis, focusing on grant writing, fundraising, and development, until a newly elected mayor cut the city arts budget to zero. So she moved to San Diego where she spent three years working in a similar capacity at the USS Midway museum. When she needed a change of scene it was off to New York and more art-related nonprofit work. “I loved that work. But I was so tired because the cost of living in New York was so much higher than in San Diego, and I was making the same amount of money. So at the same time that I was a grant writer, I was a bartender, I was hostessing, and I was modeling on the side.”

Melinda is positive and kind-hearted and has this great habit of showing up with a beautiful and delicious cake in hand; something she made special for the occasion. She’s also really supportive, and puts much time and consideration into being of service to her friends and to the greater community. When she’s on your team, she’s on your team. Needless to say, she’s deviant through and through. Leading up to this talk, I knew little more than this. We’re easing in, cruising the periphery as we settle into our reciprocal roles — discloser and inquirer. I inquire about the number of hours she was working while juggling those four gigs.

“Oh I don’t even know. I was just going from one job to another. I would leave at 6 a.m. and some nights I would get back at 3 a.m. And different modeling gigs — they would tell you that it would be six hours but it would be fourteen hours. And then sometimes at the end of the day they wouldn’t even pay you. They would just be like, ‘Oh, do you want to keep this jacket from the video shoot?’ I wasn’t in modeling very long because it’s so… I don’t want to say exploitative… It’s unchecked. It’s completely unchecked. You’ll tell somebody that your day rate is 450 and then they’ll give you 300 dollars in gift cards and no actual money. And it’s so superficial — by definition. It just felt so off for me. I still have friends in the industry who excel at it, and I really admire them. But my heart wasn’t in it. And if your heart’s not in it then it’s difficult to do.”

How was bartending?

My particular experience was awful. I worked at this bar in the financial district right before Hurricane Sandy. Nobody goes out to drink in the financial district anyway, and then after the storm that part of the city had been hit so hard by the hurricane that it was practically deserted. Some nights I would not open a single check. I would just be there by myself.”

Did you read or something?

“Yes, I love to read. So I pretty much read all night.”

What do you read?

“Everything. Right now I’m reading American Psycho for like the umpteenth time. I love that book. The prose is just so…meandering. It goes on and on and on. He’ll go on for pages and pages about an album that he loves. And then in the same breath he’ll just switch completely to some delusional episode that he’s having on the street. And then he’ll talk about shoes for another four pages. So whenever I’m stressed out or anxious — which is a lot — I read it. Because it’s easier to turn off my brain with that book than with anything else.”

Almost in a meditative way?

“Absolutely. Yeah, that’s a really good way to describe it.”

When we hit upon the subject of books there’s a change in Melinda’s voice and posture. She comes alive, describing the great books she’s read, why she loves them, and naming some of her favorite writers. We have arrived. Reading is the portal.

“I read this really funny book called Hyperbole and a Half. It’s a graphic novel. It was written by this thirty-something girl who has anxiety, and I can relate to that because I’m a thirty-something girl who has anxiety. It’s these really child-like illustrations of her daily life. She draws stick figures and it’s very raw. It’s very relatable but it’s really really funny. She writes about real situations that make her anxious, but somehow the way she writes it, it’s human and it’s lovely. I really needed to laugh when I read it and it was so great. It was referred to me by another friend who is a thirty-something woman with anxiety”

She continues, touching upon a collection of short stories by Roald Dahl that she loves. When she pauses to think of other books or authors, I double back, asking about her anxiety. She’s right there with me, jumping in and speaking candidly.

“I’ve always been an anxious… I was an anxious kid, I’ve been an anxious adult. I spent a long time trying to fix it, and that just made me sad. Depressed, even. It made me feel like there was something wrong with me. But once I realized that it wasn’t really a problem and sort of embraced it and learned how to manage it rather than try to fix it, I felt so much better.”

I bet.

“And it’s only been in the last few years that that’s happened for me. I got involved in a therapy group for survivors of childhood sexual trauma, and that changed everything. I think before I got involved in that I was really in denial about what had happened to me as a kid. It was sort of a twelve-step program and there were other survivors in it as well, and some of them were also thirty-something women of color. So for the first time, I met people like me and had a support system like I’d never had before. I’d never really been able to relate to anybody else about [it]. The therapist that led the group was great. Knowing all those other women — I’m still really close with some of them. We sort of taught each other. Because most of my anxieties come from that — so we sort of taught each other that anxiety is not a brokenness. It’s just… Some people are anxious some people are not. It’s a personality thing. I’ve learned to be more forgiving and kinder to myself. And honestly, I think it was part of what let me allow myself to switch my career and start learning pastry and becoming a pastry chef.”

Photo by Chris Keohane

Just accepting yourself as you are and then—

“Yeah. I mean both of my parents are successful professional people. My father is an attorney. He’s had his own firm for longer than I’ve been alive. My mom has been a business consultant. She has multiple degrees and has had her own businesses for years. My aunt: always super-successful. She had multiple PhDs and spoke a million languages and traveled the world. So I always felt like I was expected to be proper and academic and successful at a white collar nine-to-five job. Nobody ever told me that. It was just something that I convinced myself was expected of me.”

Well the education structures and social structures all reinforce that concept too.

“And I went to a Catholic school in Indianapolis where my sister and I were one of maybe a dozen non-white people. So we felt like we had to try that much harder to fit in; to normalize ourselves. I didn’t really know anything else. I spent most of my life feeling like I needed to fit into this little box of: be proper, be polite, be nice, be together all of the time. And be smart and impress everyone. And then I graduated from college and I was living on my own and I was doing the administration thing and I was like, ‘This is not really what I want.’”

It was at this point that Melinda’s aunt intervened. She had overcome cancer once. But when it returned she told the family she didn’t want to fight it again. “She said she didn’t feel like herself when she was on chemo. She said she felt like the color was gone from everything, the taste was gone from everything, and she told us, ‘I would rather live a few good years as myself than to live twice as long in that gray existence.’ And we all understood. How can you fight somebody on that?”

I think a lot of people do fight on that.

“It was really heavy, but we all supported her. I went home [to Indiana] a couple times to visit her, to spend time with her while I still could and while she was still lucid.”

You were really close with her?

“Very. She was like a second mother to me. She wasn’t married, she never had any kids, so she just wanted to be there for my sister and me as much as she could. She moved from Denver to Indianapolis to help raise us. She was the very definition of the cool aunt. She had tattoos and she had a Jeep that didn’t have the top on it. She was the one who taught me how to bake. My mom cannot cook for anything. I love her to death, but she doesn’t know anything about cooking. When I was little, either my aunt would come over or I would go over to her place and we would make cookies. We would make bread. We would make cheesecake. She taught me so much. When she started getting sick again she sat me down. She was like, ’I know you. I can tell you’re not happy doing what you’re doing. That’s ridiculous. You’re young. Don’t waste all of your time on this. I just want you to be happy. I’m sick, I’m dying, I never had kids, I never got married. I did a lot, but I never did everything that I wanted to do and I don’t want the same for you. I want to do what I can for you to make sure that you are happy and doing what you want to do.’”

Together they weighed the pros and cons of two different options for Melinda: going back to art school and getting a masters in visual art and painting, or going into culinary school. She opted for culinary school, which was a combination of several of her creative interests. Melinda had attempted to get various loans but nothing was coming through. “I was really upset and I was in SoHo walking up Broadway and she called me to tell me that she was going to give me the money. She was like, ‘I’m dying. Money, I can’t do anything with it now. I don’t need it. Consider this our journey that we’re taking together.’ I just stopped on the sidewalk and started crying. I think I went over to Crosby Street and sat down on a stoop and cried by myself with my phone for a good ten minutes. I mean, happy tears. I was just feeling a lot. So yeah, she gave me everything I needed to go to pastry school. It was a nine-month program and Emily passed away a month into it.”

“I talked to her the week before and she told me she knew it was going to happen. She was like, ‘I don’t want this to detract from your studies. I’m still going to be there with you. You’re doing this for both of us. Whether I’m there or not, you need to stay focused.’ I remember I went into class the next day and I had her teaspoons in my chef-jacket pocket. It was so hard but it was so special. Every time I make a cake, every time I make anything, I know she’s there with me. I’m still doing it for her and I think that’s one reason why I’m so driven to make this really happen. Because I couldn’t have done it without her. Literally. So, I want to do it for me but I also want to do it for her. When she passed away she left me her entire kitchen. All of it. I used her Kitchenaid stand mixer to make this cake.” Melinda arrived with a beautiful cake and it’s sitting beside my phone in the middle of the table and we’re going to eat it during our talk.

When you said “make this happen” does that mean having your own—

“Just making cakes for people, being a part of people’s celebrations, bringing them joy in this way that I know how to do really well. People order cake for happy and hopeful occasions, mostly. If I can be a part of people’s celebrations in that way, if I can make a cake for someone and present it to someone, and they can be like, ‘Wow, oh my god, that’s beautiful! Not only is that beautiful, it’s delicious. I’m going to remember this, and I’m going to tell everyone I know about this because it’s special.’ That’s what I’m after. I just want to be a part of people’s joy, however cliché that sounds. Occasionally when I get super-anxious and have trouble keeping my anxiety in check, I’ll call my mom or sometimes my sister and I’m like, ‘Why am I doing this? Nobody cares about cake. Cake can’t change the world. I’m not saving lives. I was doing more meaningful work as a nonprofit grant writer.’ I only get flashes of that, when I’m really really in the middle of a panic attack, or when I’m having really bad anxiety.”

But beyond the ability to be creative, it’s the sharing of joy?

“I think it’s about fifty-fifty. The creative fulfillment side comes from me growing up as a creative kid, and I… When I was growing up I had an extended illness. I got really really sick when I was ten years-old, and I spent a lot of time in hospitals. I couldn’t go outside and play. I was in a wheelchair some of the time. My mom wanted to make sure that I was still occupied and that my hands were always busy. She hated seeing me like that. So she and my aunt bought me paints, canvases, clay; all sorts of things. The hospital that I was in had art therapy, so I learned ceramics, things like that. I remember she bought me this big craft table that could either go on the floor or it could go up over my bed, and she filled it with modeling clay — those different little polymer modeling clays that you can put it in the oven and harden. I would sit and just play with that for hours. I remember one year I made a whole series of little tiny pigs. One was wearing a leather jacket, one had tattoos, one was like a flower child pig, and one was like a seventies disco pig. There were probably fifty of these little things. I would just make little things because I didn’t have anything else to do. I made a whole little series of wild animals — lions and tigers and bears, etc. I loved The Muppets when I was little and made all these little clay pencil toppers of Gonzo and Kermit and Miss Piggy. I started making jewelry for my friends. The little figures that I made are exactly the same as some of the cake toppers that I make at work now. I feel like my education hasn’t been a traditional one but everything I’ve done has sort of led up to this.”

The illness was a sinus infection that spread into her brain cavity. First she was sick at home for a couple of weeks. “Then one night I got up to go to the bathroom and I sat up and I put my legs over the side of the bed and I went to stand up and I stumbled and collapsed. I remember sitting on the floor just being fascinated that my legs wouldn’t do what my brain was telling them to do. I thought it was weird, but that’s all. My mom came in to help me and she just flipped out. Of course. We drove to the hospital and they did a scan right away. I remember looking at the image and it was like a black cloud was coming down over my brain. I wasn’t scared. I was too young and I was doped up already. They told my mom, ‘We have to transfer her to a children’s hospital and we have to do surgery tonight. I was in surgery for about nine hours. The swelling afterwards was severe. They had to remove several skull plates to let my brain try and heal without further damage. The infection ended up coming back; and even after it cleared up, I was in and out of hospitals for a few years while they repaired my skull.

They had to do that more than once! How many times did they do that?

“Twice, I had surgery for the infection. The medical storage unit where they put my skull plate wasn’t the right temperature or something. The tissue deteriorated, so they couldn’t put it back. And you can’t really put metal skull plates in kids because they’re growing so quickly. So they did all these experimental procedures to replace my skull with artificial plastic materials. The first few times they did that surgery, it failed. The stuff they used is called bio-resorbable bone replacement material, and it’s actually made from a mineral similar to coral, so it’s organic. The good thing about that is that my own cells would replace it eventually and there was no chance of rejection after healing. The first time they did it, it didn’t set correctly. It collapsed or something, so they had to remove it. The second time, it still didn’t set. There’s a huge chunk of time I don’t remember from this whole thing, but my mom told me that they did the repair surgery at least five times before she lost count. In the end, it still didn’t set quite right but it wasn’t putting pressure on or damaging anything, so they left it like that. It was fine, but my skull is still… There’s a big divot here, there’s a divot back here. I have scars that go like an “x” from here to here and from here all the way back here. It was such a bad infection that it started compromising the brain tissue up here and that’s why I couldn’t walk that night. I was so young and I was on so many drugs that I still don’t completely understand, and my mom doesn’t like to talk about it.”

That sounds like a fucking disaster.

“Yeah, it was pretty bad. And when I was sick I was also taking so many different drugs. Painkillers, anti-nausea medication, anti-seizure medications… Before this all happened, I was deathly afraid of needles, but I was having my IV changed so many times a day that my arms were black and blue. I still remember the sensation of my veins burning and collapsing. At one point they had to stick me in the bottom of my foot because all my other veins were shot. Eventually they put a port in my chest. And somehow, my blood levels went unchecked. I was overmedicated. I became sort of drug dependent and had to be weaned off of certain medications, sort of a rehab thing. I hesitate to call it full blown addiction, but it was certainly a dependency thing. It was horrible. I don’t know how people who are addicts go through what they go through. Addiction is a terrible disease, and withdrawal is a motherfucker. And I was eleven!”

Was it like shaking and vomiting and that kind of stuff?

“Some, I think. But mostly memory loss. I have six months of my life that I don’t remember. Between fifth and sixth grade.”

And that’s not because of the surgeries, that’s strictly because of the drugs?

“It’s because of the drugs. I’m mostly fine but sometimes I have migraines as a result of everything that they’ve done to my head. In my twenties they were much much worse. I was seeing several different neurologists and neurosurgeons who were just trying to get the whole thing in check. They put me on this different cocktail of drugs and I had to be weaned off of that as well.” (At this point I’m fairly well dumbstruck.)

“I still feel like it affected my short-term memory and I definitely feel much less eloquent than I was before. I find myself searching for my words a lot more than I did before. Yeah, that sucks. And from what I understand they were unsure that I would walk again, at least not the way I did before. But one of my nurses one night noticed my little toe on my right leg was moving. So they paired me with physical therapists who started moving my muscles and rehabilitating me. I eventually gained the ability to walk and then everything else. I think looking at me now you wouldn’t be able to tell.”

I had no idea.

“It happened. I still can’t believe it sometimes. But the silver lining of that was that I would spend all of my time painting and sculpting and drawing and doing all these things just because I couldn’t do anything else. And I ended up really enjoying it and it’s a big part of my life and has shaped who I am.”

I mention the concept of katabasis from ancient Greek literature — returning from the underworld with heightened knowledge. Melinda shares her own classical reference. “One of my favorite books of the time was The Aeneid. The hero, Aeneas, his purpose in life was to suffer and endure. It was never to end the suffering. It was never to figure out the source of the suffering. His destiny was to suffer and endure. And I love that. I actually want to get a tattoo of that. Of the latin phrase, not just “suffer and endure.”

Like on your knuckles.

“Suffer and endure! I could pull that off right! I’m hard enough for that. I think once we stop fighting [the idea] that part of life is suffering, and we just figure out how to manage it — I mean it’s the same with anxiety. You just have to figure out how to go with the flow and you become so much happier. Especially in the last few years, it’s been a big part of who I am in general and who I am as an artist and who I am as a pastry chef. It’s just learning not to fight all of those things that we’ve been taught that are false. That’s an important part of my story.”

It’s cool to get to that place.

Photo by Chris Keohane

“Yeah. The illness, and what I went through with my aunt, and what I’ve gone through with my mother, and then what I went through while I was sick. I was molested by my mother’s ex-husband. My parents got divorced when I was five, and my mom remarried when I was six to this man — and I never liked him. He [was] more or less my father figure. He started doing what he did when I got sick. He would say, ‘I’m checking your port. I’m checking your bandages. But don’t tell anybody about this.’ And he would always say, ‘They can’t know — it’s got to be our secret. Your mom would be jealous. Your sister would be jealous.’ I didn’t know what to do. I was half my body weight. I was sick. I was doped up. And then it went on — even after I recovered — it went on for a little while.”

“One day he came to my room and I was like, ‘Don’t touch me, don’t anything. I will tell everyone.’ He was very protective of his image, and that scared him when I said that. So it stopped happening but it was always very tense between us. He was still married to my mom and still very much a part of my life, but I never said anything because I was scared. He was such a pillar of the community. And, you know, anybody who goes through trauma like that when you’re young, and especially when it’s your parent figure, you don’t know what to do. I think that’s where most of my anxiety stems from. I was holding it in for such a long time. It was literally the only thing that I’ve never told my mother [right away]. We’re so close. Everything I’ve gone through, everything I’ve ever done, everything else that’s ever happened to me, I had told her. But this, I had never told it to her. It started really, really getting to me in my early twenties and I started seeing a therapist for it. My therapist was getting me emotionally ready to tell her, and then my aunt got sick. And my aunt is my mother’s best friend and youngest sister. I was like, ‘I can’t do both of these things to her at the same time. She can’t lose her sister and her husband at the same time. I feel like it would just fracture our family entirely.’ I carried a lot of guilt about that for a long time.”

“And then my aunt passed away and I went home to be with my mom. One night we went to the theatre and dinner, sort of having a mother/daughter date, and I just told her everything. And she was with me one hundred percent, right from the moment the words came out of my mouth. No questions. No hesitation or doubting. Knowing her and looking back at it, I don’t know what I was so afraid of. I remember we were on the way to the airport for her to drop me off so I could go back to New York. I got on the plane, went back to the city, and never saw him again. Now my immediate family is just me, my mom, and my sister. But we’re closer than ever. Talking about it has made me a better person. It’s taught me how to deal with my anxiety. It’s taught me how to deal with the sexual trauma. I’ve been able to help other people deal with their experiences because of it. I can be a mediator, and a support for people when they need it.”

How did you stay cool growing up with that? You didn’t really have a comfort space. You come home and there’s this—

“I read. I would always lock my door, and I would read. When I was a teenager mostly that’s what I would do. And sometimes I would draw. I didn’t really make this connection until a few weeks ago, but I would always draw on myself. Just like my tattoos!I had these gel pens, and I would draw different designs up and down my arms and my hands and things. I would draw on my friends and classmates, and that’s the only thing I ever got in trouble for in school. It was ‘against the dress code.’”

Melinda never imagined that she would get into tattoos. It had never been an interest of hers. “But looking back and knowing that I used to do that as a child, it completely makes sense to me now. The way that I fell into tattoos was weird. Because I didn’t actually get my first tattoo until I moved to New York, so I was twenty-six. A good friend of mine from college passed away, suddenly. He had a brain aneurism and never woke up. I felt like he wasn’t with me — I couldn’t feel him and that was just destroying me and I didn’t really know how to process that. I thought about it for a year or so. I thought of different things I could do. And then I was finally like, ‘I’ll get a tattoo. I’ll get a memorial tattoo for him.’” She came up with an idea for a two-part tattoo, doing the smaller part first to see how it settled with her prior to continuing.

“I loved it from the moment she started tattooing it. It made me feel so much better, and it also reminds me to live my life how he did. He was always putting other people ahead of himself; always serving others. I also think the physical tattooing part has something to do with when I was a kid and when I was in the hospital all the time. I hated needles. I would psych myself out. Even if all I had to do was get a central line or a shot the next day, I would be so nervous. ‘Oh my god mom, I’m gonna die. What if something goes wrong?’ It was a never a fear of the surgical procedures themselves. It was always a fear of all the needles involved! But then when I started getting tattooed it was like… I don’t know, it’s hard to describe. It’s almost like a pleasure from pain kind of thing. Because when you get a tattoo your body gets filled with tons of adrenaline. You have so many endorphins just running through your blood afterwards. It completely removed that fear. I look forward to it now.”

Adaptation is a physical or behavioral alteration provoked by external stresses that become written, historically, into those new forms or habits. There is a manifest link between Melinda’s adult interests and her childhood adaptations. There is history written into her love of books, tattoos, and being a pastry chef. The calmed response to endless readings of American Psycho is the most recent among a lineage of soothing reads originally done behind a locked bedroom door. The empowering endorphin rush of the tattoo needle is an evolutionary descendant of all those fear-inducing hospital needles and a creative mind that playfully drew patterns on skin while attending a strict Catholic school. And the decision to become a pastry chef is interwoven with childhood joys shared with a loving aunt whose last deed was to ensure that Melinda pursued her dreams. She did not hide from past traumas, because you can’t hide from history. Melinda adapted instead, morphing childhood coping mechanisms into positive adult pursuits. I ask her the biggest lesson she took away from it all.

“I think embracing the anxiety, embracing the creativity, embracing yourself naturally and not fighting it, is so important. Not trying to make other people into something else either; not trying to make yourself into anyone else; not trying to change situations into things that they aren’t. If you’re struggling, learn how to incorporate it into your life. There are certain struggles that are worthwhile, certainly. But your flaws should not be a part of that.”

It’s like accepting the reality and then moving from there. And if there are legitimate things that you need to move through, denying it or rebelling against it is not necessarily the most effective way.

“Yeah, yeah… Yes! That’s what I mean.”

And not necessarily beating yourself up over the fact that there are certain things about your reality that the greater world doesn’t understand and that maybe aren’t even problematic.

Photo by Chris Keohane

“Right. Because my mom says to me all the time when my anxiety does get really bad and when I worry about, ‘Is there something else I should be doing with my life?’ she’s really good at getting me to focus. She just says, ‘You dealt with illness, you dealt with addiction, you dealt with sexual trauma, you dealt with losing someone that was very very close to you, and you are okay. You are more than okay.’ She’s like, ‘You are a success story. There are so many different directions that you could have gone. You could have given in to all of this. You could be homeless, you could be addicted to drugs… There are just so many things that you could have done but you prevailed over all of it.’ And I know that even if I had been any of those things, it doesn’t have to end that way. It would just be another struggle or two of three to overcome and write into my story.”

“I think suffer and endure applies to that too. Bad things are always going to happen. Hopefully you can learn from them and learn how to turn them into positives. Too many people expect that they will hit this peak where they’re happy and it will just be a plateau. ‘Alright, this is how the rest of life goes. I’m just happy, happy, happy.’ People expect this constant stream of it. There are so many people who are like, ‘What do I need to do to be happy? What needs to happen in my life to be happy? What are the steps that I take to be happy?’ There’s no flat line of happiness. And that’s okay.”

And because of that perception of life the social norms that are imposed are, ‘You’re not aligned with this supposed happiness. What do you have to tweak in yourself to get to that happy line?’

“Yeah, but that’s just not true. And, I have become happier since accepting that. It’s backwards.”

Meaning that it works the other way around. Facing up to life’s difficulties is the happier, more rewarding approach. You must go through, because you can’t go around. Suffer and endure.

Get Deviation Issue 002 (Print or Digital)

[fbcomments width="100%" num="10" ]